|

Entry written by Joyce Butler and Jennifer Graff, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse.

|

Research & Writing ProcessWho is Carole Boston Weatherford?

|

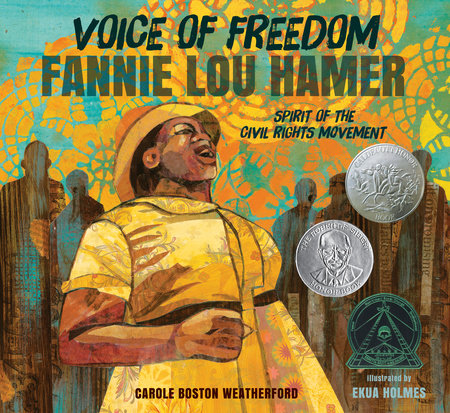

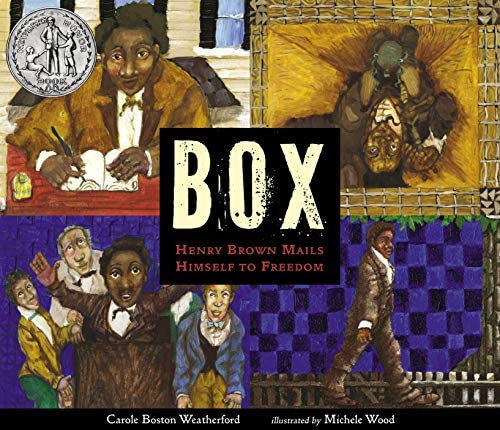

Her most recent picturebook biographies in verse are the 2021 Newbery Honor, BOX (2020), illustrated by Michele Wood, and the 2021 Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honor, R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul (2020), illustrated by Frank Morrison. These two picturebook biographies follow a legacy of award-winning biographies, such as Moses: When Harriet Tubman Led Her People to Freedom (2006), illustrated by Kadir Nelson, Becoming Billie Holiday (2008), illustrated by Floyd Cooper, Schomburg: The Man Who Built A Library (2015), illustrated by Eric Velasquez, and Gordon Parks: How the Photographer Captured Black and White America (2015), illustrated by Jamey Christoph. Other critically acclaimed or award-winning nonfiction picturebooks include Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre (2021), illustrated by Floyd Cooper and Freedom in Congo Square (2016), illustrated by R. Gregory Christie, among many others.

Carole is currently a Professor of English at Fayetteville State University, where she works with current and future teachers as well as aspiring writers. To find out more about Carole, access teaching guides and videos, and get to know her and her son, Jeffery, a poet, illustrator and co-creator of You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen (2016), visit cbweatherford.com.

Carole is currently a Professor of English at Fayetteville State University, where she works with current and future teachers as well as aspiring writers. To find out more about Carole, access teaching guides and videos, and get to know her and her son, Jeffery, a poet, illustrator and co-creator of You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen (2016), visit cbweatherford.com.

Carole's Process & Artifacts

|

|

Our interview with Carole Boston Weatherford includes discussions about her connections with the significant people about whom she writes, her research and writing processes, and her intentional craftsmanship of narrative voice. Interspersed throughout the interview are stories that further personalize Carole’s artistic process as a poet, biographer, storyteller, and activist. As with many conversations, we often move back and forth between topics. Throughout our conversation, Carole focused on the following topics related to researching and writing biographies, particularly Voice of Freedom.

|

- Her inspiration for writing Voice of Freedom

- The connections between Voice of Freedom and her 2010 book, The Beatitudes [2:00-4:45];

- The need to preserve Fannie Lou Hamer’s legacy [4:52-7:00]

- Her spiritual connection to Fannie Lou Hamer [46:41-47:12], & [52:43-54:32]

- The intersections of her writing and research processes involving primary and secondary multimedia sources [7:50-13:07], [44:05-47:12], & [51:55-52:43]

- The challenge of finding sources [36:20] & [44:07].

- The art and science of writing biographies

- Deciding when to use 1st person or 3rd person point of view [19:55]

- Crafting authentic voice and expression [13:07-19:05]

- Channeling voices from the past [44:50-51:54] & [52:43-54:31]

- Writing hybrid genre books [23:25-27:00]

- Conveying “emotional weight” and “factual burdens” via poetic style [32:56-35:55]

- Her reasons for including specific experiences and events in Voice of Freedom [27:58-32:55]

- The surprising discovery of Fannie Lou Hamer’s visit to Guinea and importance of that trip [40:14-44:05]

- The necessity of connecting the past to the present [55:20-61:45]

The artifacts shared below reflect the primary resources Carole used when researching Fannie Lou Hamer.

Craft & Structure

Narrative Voice

|

Point of view — the narrative voice of a biography — is instrumental in helping readers understand the author’s perspective, or how the author wants readers to “see” the person they are writing about. The narrative voice helps cultivate personal and emotional connections between readers and the featured individual. While third-person is probably the most common narrative voice in verse or prose biographies for children, first-person voice is also present.

Weatherford uses both first and third person in her biographies in verse. The narrative voice she uses is often informed by how she wants to “recreate their voices” [18:25], how “the character speaks to me” [20:00], and how she wants the reader to experience the character [21:07]. While many of her biographies are in third-person, she prefers first person narration because it offers “the most intimate way of telling the story” [22:10] and offers readers a sense of immediacy, as if the reader is present as events are happening. |

With students, reread Voice of Freedom and discuss when and how the first-person narration creates a sense of intimacy or emotional connection to Fannie Lou Hamer, her family, and her fellow civil rights activists. Additionally, discuss the ways in which first-person narration might help readers feel as though they are participating in — rather than observing — Fannie Lou Hamer’s world.

Compare and contrast some of Weatherford’s first-person and third-person narrated biographies and document how feelings of intimacy and distance are evoked through the narrator. Have students experiment writing a pair of brief poems about someone who is important to them. Students can write one poem in first-person and the other in third-person. During Writer’s Workshop, have students conference with one another about their use of narrative voice in their two poems. Follow-up with individual or group reflection and dialogue about their writing processes in terms of decisions, discomforts, creative freedoms, and their responses to the poems as readers. |

First Person Verse with Quoted Speech

|

The use of first-person in Voice of Freedom allows for a seamless fusion of Fannie Lou Hamer’s quoted words in italics and Weatherford’s poetic descriptions. Such unions offer vivid portraits of Fannie Lou Hamer’s thoughts and experiences of hardship and triumph with an emotional intensity grounded in verbal realities.

|

With students, reread poems that include quoted speech of Fannie Lou Hamer, such as “Delta Blues” (p.3), “My Mother Taught Me” (p.5), “On the Move” (p.16), “Running” (p. 23), “1964 Democratic National Convention, Atlantic City, New Jersey” (p.26), “Black Power” (p.33), and “No Rest” (p.36). Discuss how Fannie Lou Hamer’s italicized words align with Carole’s poetic descriptions, contribute to the emotional tones within a singular poem and collective poems, as well as help deepen one’s understanding and the significance of the events. Listen to audio or video clips of Hamer’s interviews, speeches, and testimonies spanning multiple years and for different audiences, and discuss how Weatherford captures Hamer’s spirit in her poetry.

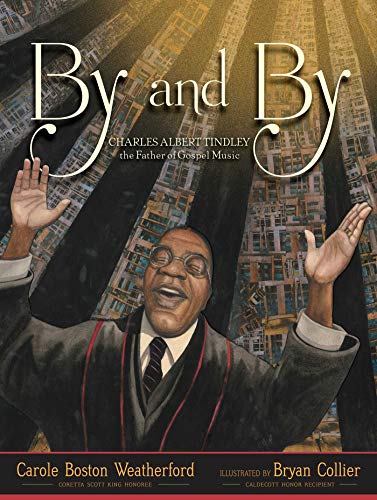

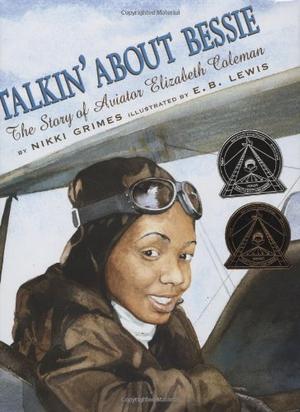

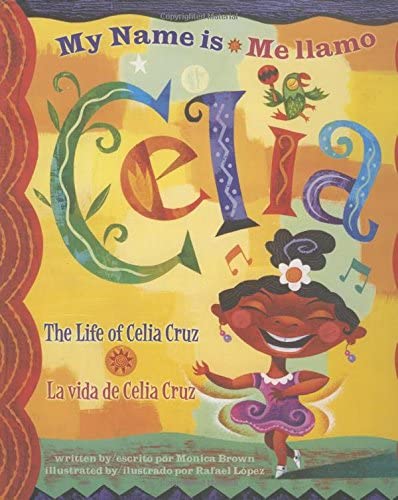

Further engage in an exploration of the affordances and limitations of biographies written in first person verse or prose. Read more of Weatherford’s first-person verse biographies, such as BOX (2020) and By and By: Charles Albert Tindley, the Father of Gospel Music (2020), or other award-winning biographies in first-person verse such as Talkin’ About Bessie: The Story of Aviator Elizabeth Coleman (2002) written by Nikki Grimes and illustrated by E. B. Lewis. Also consider reading award-winning, first-person prose biographies such as My Name is Celia/ Me llamo Celia: The Life of Celia Cruz / La vida de Celia Cruz (2004) written by Monica Brown and illustrated by Rafael López. Consult the back matter for information about the first-person characterizations and quoted material and discuss how the authors’ cultural and socio-historical connections with their subjects contribute to the books’ intimacy, cultural authenticity, and historical accuracy in form and expression. |

Writing Style

|

Writers often shift their writing style to engage the reader and match the type of information they wish to share. In Voice of Freedom, Weatherford uses both prose and verse to connect with her audience. During our interview with Weatherford, she shared with us that she uses prose to convey factual information because of the volume of information she wants to share. However, she prefers verse when setting up the physical and emotional landscapes, such as Hamer’s memories. Readers will recognize Weatherford’s prose in poems such as “Fair” (p. 6), “On the Move” (p. 16), and “The Beating” (p. 21). Weatherford’s use of verse is noticeable in poems such as “Delta Blues” (p. 3), “My Mother Taught Me” (p. 5), and “Worse Off Than Dogs” (p.10).

|

Have students select one of the poems in Voice of Freedom, such as, “Fair” (p. 6), “On the Move” (p. 16), “The Beating” (p. 21), “Delta Blues” (p. 3), “My Mother Taught Me” (p. 5), and “Worse Off Than Dogs” (p.10) to read. Invite students to explore the difference between Weatherford’s use of prose and verse. Students can then share if they believe their selected poem is prose or verse, their reasons for those determinations, and how the prose or verse contributed to their responses as readers.

|

Documenting Chronological Order

|

Knowing what happened and when is important in biographies, especially when highlighting an individual who experienced and accomplished a lot in a short period of time. In Voice of Freedom, Weatherford included many of Fannie Lou Hamer’s life events, particularly events that “were the most dramatic . . . impacted her most deeply . . . and through which she [Fannie Lou] contributed most significantly” (27:58 in video and p. 8 of the interview transcript). Biographers, especially those who write in verse, may use a variety of time indicators (e.g., specific dates, ages, temporal phrases such as “a month later” or “later that year”) to mark significant events.

|

As a class and/or in small groups or pairs, reread the poems. Then create a timeline of Fannie Lou Hamer’s life. Document key events, noting the language Weatherford uses to convey these events in chronological order without disrupting the rhythm and pacing of the poems and the overall biographical narrative. Students can create interactive timelines via school-approved apps or other digital programs. Students can also make a picture or image of an event, label it, and create a visual timeline around the room.

Time permitting, review the timeline of additional significant historical events in the backmatter. Compare your class timeline with the backmatter timeline. Identify which of Hamer’s life events were included in both the poems and the backmatter timeline, which are only mentioned in the poems, and which are included only in the backmatter timeline. Then discuss why some events are in both places and why some events are in one or the other location. |

Content & Disciplinary ThinkingThe more we re-read Voice of Freedom, the more we identify multiple entry points that would enrich any social studies or U.S. history unit focused on the Civil Rights Movement. We also recognize how “the past” of 50 years ago is very much still the “present” in 2021. In less than 40 pages, Voice of Freedom includes details about the dehumanization of Fannie Lou and her family as sharecroppers in Mississippi who lacked access to quality healthcare (see the She Persisted: Claudette Colvin entry for more information). These pages also mention Hamer’s involuntary sterilization, a procedure so commonly forced upon Black women in Mississippi that it was known as “Mississippi Appendectomies.” Additionally, readers witness the powerful transformation of Fannie Lou Hamer from resigned sharecropper to the “spirit of the Civil Rights Movement.” Guided by her mother’s advice, continuously uplifted by spirituals, and emboldened via education and the pursuit of justice and equity, Fannie Lou Hamer perseveres. Below we offer a few of those entry points and additional resources to illustrate some of the past-present connections with regard to equity and justice.

|

Youth Organizations: From the Founding of SNCC to Youth Activists Groups of Today

|

The voices of youth have led powerful movements for change since the 1960’s, such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC--pronounced “SNICK”). Led in part by Fannie Lou Hamer, SNCC young adult leaders committed themselves to advancing the Civil Rights Movement. Today, both individuals and youth group organizations continue to use their voices to promote positive change in the world. For example, Greta Thunberg, at age 16, implored world leaders at the UN Climate Change Summit to prioritize climate change before it is too late. Other youth-led organizations advocating for positive changes around the world include groups such as

|

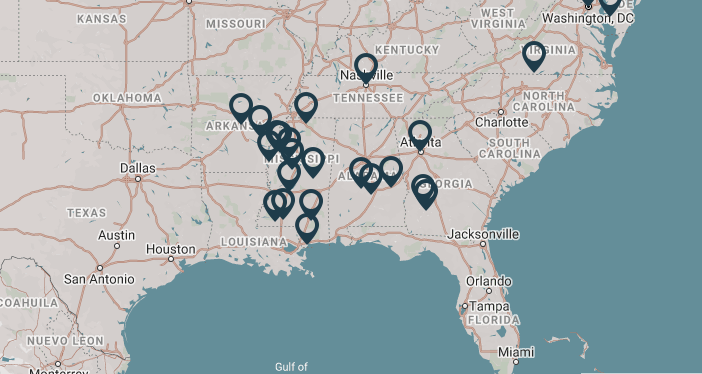

Have students in groups or as an entire class explore the beginnings of SNCC with the interactive map below to show students how change can start small and grow quickly. By clicking on each marker, students will learn who worked at that site as well as the events that took place there.

With students, discuss the importance of how one voice or many voices can make change happen. Share Fannie Lou Hamer’s voice in the poem “SNCC” (p.18) and Greta Thunberg’s speech to world leaders at the UN Climate Change Summit and discuss how their voices affected change.

|

|

The SNCC organization, founded in 1963, strengthened the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi by establishing small, working groups in many parts of the South to advocate for widespread change. SNCC, along with powerful youth movements of today have also played an important part in positive changes for our world. In books such as John Lewis, Andre Aydin, and Nate Powell’s March (Trilogy) (2016) readers are introduced to Martin Luther King’s peaceful protests for change and equality. In Let the Children March (2018), Clark-Robinson addresses the 1963 Children’s Civil Rights March in Birmingham where a group of children protest segregation laws. In I am Malala (2013), Malala Yousafzai uses her voice to fight for girls’ education around the globe.

|

Have a book club month that meets once a week to discuss how one voice (Greta Thunberg), small groups (SNCC), and eventually larger organizations (Alliance for Youth Action, among others) can effect positive change in the world. Consider books such as John Lewis and colleagues’ graphic novel trilogy, March, Evette Dionne’s Lifting as We Climb: Black Women and the Ballot Box (2020), Monica Clark-Robinson and Frank Morrison’s Let the Children March (2018), and Yousafzai and McCormick’s I am Malala (2013).

|

Freedom Schools

|

Freedom schools propelled many young people to join the Civil Rights Movement. Formed in December 1963 out of concern for equality for all Black persons, SNCC members created the Freedom Schools to empower youth voices. Some have made parallels between the Freedom Schools and Freedom University, an Atlanta, Georgia-based, “modern-day freedom school,” whose mission is “to educate and empower undocumented students by using their voice to fulfill their human right to education” (Freedom University, n.p.).

|

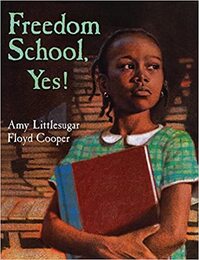

Read aloud Freedom School, Yes! (2001), written by Amy Littlesugar and Floyd Cooper, and/or share a few of the brief biographies in Let It Shine: Stories of Black Women Freedom Fighters (2000) written by Andrea Davis Pinkney and illustrated by Stephen Acorn. Discuss how these women became agents of change to promote equality in education. Consider discussing the character traits of these prolific women and how these traits might also encourage change. Additional resources to consider include The Biography Clearinghouse entries on Congresswoman Barbara Jordan (So What Do You Do With A Voice Like That?) and civil rights activist Claudette Colvin (She Persisted: Claudette Colvin). Also consider the picturebook biography, Lift as You Climb: The Story of Ella Baker (2020) written by Patricia Hruby Powell and illustrated by R. Gregory Christie. Ella Baker was instrumental in the creation of SNCC and has been ranked as one of the most influential women in the Civil Rights Movement.

|

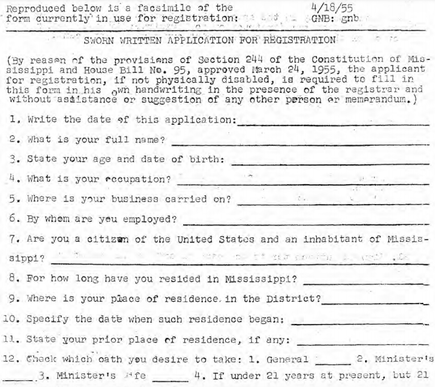

Voter Suppression: Literacy Tests and Poll Taxes

The poems on pp. 14-17 (“Literacy Test,” “On the Move,” and “The Price of Freedom”), illuminate how voter intimidation, literacy tests, and poll taxes served as societal and legal gatekeepers, preventing Blacks and other marginalized people from voting. The ratifications of the 24th Amendment in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were meant to prohibit poll taxes and literacy tests; however, five states continued to use poll taxes in state and local elections: Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia. Within the past decade, charges of contemporary voter suppression accompany a plethora of legislative bills about state and national voting processes, Supreme Court Cases, and the yet-to-be ratified John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

Here are some additional resources that provide examples of literacy tests and poll taxes as well as contemporary court cases regarding poll taxes and voter ID laws.

Here are some additional resources that provide examples of literacy tests and poll taxes as well as contemporary court cases regarding poll taxes and voter ID laws.

Engage in discussions about the parallels between voter suppression in the early to mid-1900’s and in the 21st century. Consider using comparison charts or other graphic organizers that help document your exploration of the distinctions and similarities between previous laws and currently proposed legislation. For more local contexts, investigate the proposed legislation of your own state and discuss the ways in which that legislation may be expanding and/or restricting or disenfranchising voters' rights.

Civil Rights and the Strength of Song

Music and civil rights go hand in hand. Many songs and poems-turned-into-songs serve as lyrical acts of protest, inspiration, resilience, and hope. Referred to as the “spirit of the Civil Rights Movement” (p. 18), Fannie Lou Hamer often sang childhood spirituals, such as “This Little Light of Mine” to motivate herself and others to continue the fight for civil rights and freedom.

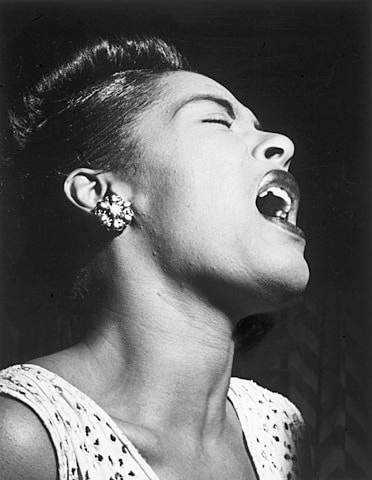

Below is a sampling of resources focused on the significance of song in the fight for equal rights from the turn of the 20th century to the Civil Rights Movement. The resources are divided into three sections. The first section offers resources that discuss the songs of the Civil Rights Movement. The second section focuses on Lift Every Voice and Sing, a poem written by James Weldon Johnson that became a song in 1900 and is considered the Black National Anthem in the U.S. The third section includes more information about Fannie Lou Hamer and four additional female singers who played significant roles in the ongoing fight for civil rights: Billie Holiday, Odetta Holmes, Mahalia Jackson, and Marian Anderson. For each of the four singers, we offer a picturebook biography, a link to an online article about the singer or the significance of their music, and video or audio clips of their songs or performances.

Use these resources during a multimedia exploration of the role of song and notable Black female singers in the fight for equal rights. Consider expanding the exploration to include musician-activists such as Sam Cooke, Bob Dylan, Joen Baez, and Pete Seeger, or perhaps musicians and their songs from other periods of activism from the 1970’s to today. Ed Masley’s February 2021 article, “25 Songs of Social Justice, Freedom, and Civil Rights and Hope to Honor Black History Month” offers some additional artists from the 1960’s and 70’s (e.g., Marvin Gaye and Nina Simone), as well as more contemporary artists such as Kendrick Lamar, Lauryn Hill, and The Roots.

Below is a sampling of resources focused on the significance of song in the fight for equal rights from the turn of the 20th century to the Civil Rights Movement. The resources are divided into three sections. The first section offers resources that discuss the songs of the Civil Rights Movement. The second section focuses on Lift Every Voice and Sing, a poem written by James Weldon Johnson that became a song in 1900 and is considered the Black National Anthem in the U.S. The third section includes more information about Fannie Lou Hamer and four additional female singers who played significant roles in the ongoing fight for civil rights: Billie Holiday, Odetta Holmes, Mahalia Jackson, and Marian Anderson. For each of the four singers, we offer a picturebook biography, a link to an online article about the singer or the significance of their music, and video or audio clips of their songs or performances.

Use these resources during a multimedia exploration of the role of song and notable Black female singers in the fight for equal rights. Consider expanding the exploration to include musician-activists such as Sam Cooke, Bob Dylan, Joen Baez, and Pete Seeger, or perhaps musicians and their songs from other periods of activism from the 1970’s to today. Ed Masley’s February 2021 article, “25 Songs of Social Justice, Freedom, and Civil Rights and Hope to Honor Black History Month” offers some additional artists from the 1960’s and 70’s (e.g., Marvin Gaye and Nina Simone), as well as more contemporary artists such as Kendrick Lamar, Lauryn Hill, and The Roots.

Overview of Songs of the Civil Rights Movement

|

Lift Every Voice and Sing (the Black National Anthem)

|

A Sampling of Female Singers, their Songs, and Their Significance

Fannie Lou Hamer

|

Billie Holiday

|

Odetta Holmes

|

Mahalia Jackson

|

Marian Anderson

|

Social & Emotional Learning

Resilience and Perseverance

|

In Voice of Freedom, Weatherford often juxtaposes hardship and resilience throughout Hamer’s journey. Known for saying “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired” (SNCC, p.18), Hamer became more resilient as she and her family endured relentless hardships and injustices. The poem “Literacy Test” (p.14), identifies how the opportunity to register to vote served as a turning point for Hamer via Hamer’s own words: “I guess if I’d have any sense, I’d been a little scared, but what was the point of being scared. The only thing they could do was kill me. And it seemed like they’ve been trying to do that. A little bit at a time ever since I could remember.”

As an advocate and leader of SNCC, Hamer not only showed resilience, but also perseverance in times of physical and emotional difficulty. Statements such as, “Hard as we have to work for nothing,There must be some way we can change things . . . . There must be something else” (“Running,” p.23) illustrate her resilience and perseverance. |

Revisit Voice of Freedom and have students identify and discuss examples of Fannie Lou Hamer’s resilience and perseverance. Invite students to discuss when they have shown resilience and perseverance and who or what helped them during those times.

|

Cultivating Empathy

One of Weatherford’s goals when choosing the topics and people to write about is to help young readers cultivate empathy (interview transcript, p. 10). There are numerous places throughout Voice of Freedom that convey Hamer’s empathy towards others, despite the violence she may have endured because of them. Those poems also help children develop empathy for Hamer and other activists risking everything--including their lives--to ensure everyone had equal rights.

As a class or in small groups, engage in close readings of one or more poems such as “Not Everyone Could Move Up North” (p.9), “Worse off Than Dogs” (p.10), “Running” (p.23), “Freedom Summer” (p.24), “Africa” (p.28), “Black Power” (p.33), and “No Rest” (p. 36). Engage in quick writes or sketches, “turn-and-talk” activities, or perhaps dramatic tableaux, where students can respond, reflect and ponder, and process Hamer’s words and feelings when she experiences these pivotal moments:

- remaining in the South to care for her mother

- being treated worse than the landlord/planter’s dogs

- casting her first vote for herself

- mourning the murder of two students she trained during the Freedom Summer campaign

- reacting to seeing Guineans free, thriving, and treating her as an equal

- discussing the concepts of hate and success

|

Enrich your discussion by also focusing on Ekua Holmes’ vibrant, textured collages that accompany Weatherford’s poems. How do Holmes’ collages, “based on or inspired by photographs” (Weatherford, 2015, unpaged backmatter--Copyright Acknowledgements), help us connect with and understand Hamer’s thoughts, feelings, and actions? How does the collective artistry of Weatherford’s poems and Holmes’ artwork affect us?

|

New Texts & ArtifactsCreating Playlists for Motivation and InspirationAs discussed earlier and reflected in Voice of Freedom, music can inspire, motivate, and unite people, communities, and generations. We use “fight songs” to help us tap into our personal reserves and inspire us to continue against all odds. Sports teams, individual athletes, public speakers, use “entrance songs” to rally themselves and the public before playing, performing, or speaking. Songs can even evolve in meaning and use, such as Audra Day’s “Rise Up.” Day originally created Rise Up as a personal prayer to help her cope with a friend’s cancer diagnosis. The song was then used by the Atlanta Falcons football team and became the unofficial anthem of Black Lives Matter in 2017.

|

In this era of digitally rich resources, invite students to create music playlists that serve as personal motivation and/or stimulus for social action. These playlists can serve as artifacts of contemporary issues and experiences important to the students while also allowing them opportunities for personal expression and to connect with the past.

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

|

After discussing the power and significance of songs in Voice of Freedom, have students generate an initial list of 5-7 songs that they listen to for inspiration, motivation, etc.

Ask students to state why they listen to each of the songs, noting the purpose and topic or issue. |

Students continue to work on their lists individually or collaboratively, revising as they think about the purpose and connection between the songs and themselves.

Consider one or more of the following activities for students:

|

Students continue to work on their playlists, poetry, and/or accompanying chart or graphic organizer, adding the reasons for the final playlist order.

Students add an introduction that discusses the purpose(s) of the playlist and the connections to the student. The final playlists can be shared with the class or the larger community. If possible, students can use Flipgrid, Instagram (Instastories), TikTok, etc. to further personalize their playlist. After experiencing each other’s playlists, the class might also want to discuss at a minimum:

|

Youth as Agents of Change in Local Communities

Voice of Freedom begins with Hamer’s own words: “The truest thing that we have in this country at this time is little children . . . . If they think you’ve made a mistake, kids speak out.” Pairing Hamer’s advocacy detailed in Voice of Freedom with contemporary youth activists, guide students in their exploration of how they can (or continue to) be agents of change in their local communities.

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

|

Using Voice of Freedom, discuss with students how Fannie Lou Hamer was a voice of change for voting rights and Black female political representation during the Civil Rights Movement.

Introduce Amanda Gorman, the First Youth Poet Laureate of the United States, to students. As a class, watch Gorman’s reading of her 2021 presidential inauguration poem, The Hill We Climb. Ask students what message they think Gorman is conveying through her poem. Use the full-text version of "The Hill We Climb" Text for students’ exploration of Gordon’s words. Discuss how Gorman uses her voice to effect change on issues such as civil rights and feminism. Begin an Agents of Change T- chart, using the headings, “Activist” and “Cause.” Ask students what issues Amanda Gorman might be advocating for in “The Hill We Climb.” Ask them about other causes they know about to include on the chart. |

Revisit the concept of "agents of change," using the previously completed T-Chart.

Watch one or both of the following videos featuring youth activists focused on environmental issues: Continue to add to the existing T-Chart or create a new chart. Engage in discussions about the choices Genesis and Mari are making, how these affect their communities, and why this classifies them as agents of change. Below are other young activists that you might want to include in your conversations

|

Discuss the importance of youth activism in tandem with Secondlineblog.org.

Have students identify local youth activists or organizations in their area whom they see as a voice of change. Consider using Global Citizen for inspiration. Have students create interview questions after they have chosen people to interview. Students will then conduct, record, and interview individuals through Zoom, Teams, Google Meets, or other digital platforms. Using their interview recordings as a resource, students can create a multimodal presentation on the group or individual to describe their advocacy work as an agent of change. Additional activities include:

|

Butler, J., & Graff, J. (2021). Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement. The Biography Clearinghouse.]