|

Entry written by Jenn Sanders, and Courtney Shimek, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse.

|

Research & Writing ProcessWho is Lesa Cline-Ransome?

She has also written historical fiction, including Finding Langston and its sequel, Leaving Langston. Many of Lesa’s books are illustrated by her husband, James Ransome, but they typically have separate creative processes, working on a book at different times. When she’s not reading or writing, Lesa loves asking questions, eating avocados (with cilantro), listening to vinyl records and live music, and spending time with her four children. To find out more about Lesa, visit www.lesaclineransome.com.

|

Lesa's Process

|

|

Watch the video recording of our interview with Lesa Cline-Ransome. In this video, Lesa talks about her writing process and decisions for this book:

|

Craft & Structure

Organizing Informational Writing with a Q & A Text Structure

|

Informational writers have several choices in how they organize their writing. The organizational structure often depends on the author’s purpose for the text and the main ideas they want to highlight. Some common informational text structures include the cause and effect structure, frequently used in explaining historical and contemporary events; the chronological or sequential text structure that lends itself to biographies or lifecycles and scientific processes; and the descriptive or topic-subtopic informational text structure in which kinds of things and attributes of those things are described in detail (Kristo & Bamford, 2004). In She Persisted: Claudette Colvin, Lesa Cline-Ransome uses a macro structure of chronological writing to convey the narrative of Claudette’s life and a question and answer text structure as the micro organization pattern. She begins almost all of the chapters with questions as the chapter titles, and then proceeds to answer that question in the corresponding chapter.

|

Have students choose an informational picturebook they have already read, or one that has been read aloud to the class. Reread the book together, looking for clues to the text structure, and try to identify how the information is organized by the author. Remind students that the text structure is often connected to the author’s purpose, so it might help to identify what the author is trying to accomplish in that text.

|

What did they say?

|

Authors may have choices to make in the kinds of dialogue they incorporate into a narrative. They may have access to primary sources that have direct quotes or dialogue documented “in the moment,” during the event, or they may have sources of dialogue from recent interviews in which a person is reflecting on past experiences and commenting on it through the lens of time and distance from the actual event. Claudette Colvin is still living in Alabama and has been talking about her story more in recent decades, so in writing about Claudette, Lesa had access to both kinds of quotes: recent interviews where Claudette Colvin was reflecting on past experiences, processing those events through her current stance, and accounts of actual dialogue that was documented “in the moment,” during the event of the bus boycott and trial.

|

Students can watch this YouTube video interview with Claudette Colvin or this reading of Claudette’s personal account of the incident and listen for things she says that are included in Lesa’s biography of Claudette.

In addition, talk with students about the ethical responsibilities authors of nonfiction and biographies must uphold. How do we include reflections or quotes from historical figures that are shared long after an event occurred? What do we need to do, as authors, to make sure readers have a sense of when this quote occurred? You might look at the backmatter of other biographies to see where other authors have found sources for direct quotes. Lesa Cline-Ransome specifically stated that she never includes fictional dialogue in her books because she wants them to be as accurate as possible. But what if an author does not have access to direct quotes from a person about whom they are writing? Discuss with the class: Would it be okay to fictionalize dialogue? What would that add to the story? What are the risks? |

The Power of Repetition

|

Repetition is a powerful writing strategy that an author can use to emphasize a point, create a tone, or draw attention to something. Authors might repeat a single word, a phrase, or a whole sentence or refrain.

For example, Lesa conveyed the prominence of religion in Claudette Colvin’s life and how she was greatly influenced by her Church growing up by including the Lord’s prayer as a repeated phrase, or mantra, in several places throughout the narrative (e.g., pp. 10, 28, 46). |

Students can reread Lesa Cline-Ransome’s biography of Claudette Colvin, looking for places the author uses repetition. When they find an example of repetition, ask them to decide what impact that repetition has on them as readers or what feeling is created by the repetition. Students can also consider the phrases they repeat in their own lives and how those phrases, prayers, or mantras reflect their own cultural backgrounds and experiences. Remind students that repetition is a writing device they can use in their own writing, in any genre.

|

Content & Disciplinary ThinkingAs we read Lesa Cline-Ransome’s biography of Claudette Colvin, we were struck by Claudette’s knowledge of Black history and how this history gave her the courage to refuse to give up her seat. She later credited her history teacher, Ms. Geraldine Nesbitt, for spending the month of February celebrating Black History and teaching her about Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and her Constitutional Rights. We began to wonder about the divide between U.S. history and Black history in our current curricula and who or what often gets left out of Black history in school today, or whose story is included but told without nuance or complexity. After all, Colvin herself is frequently left out of textbooks, curricula, or resources regarding the Montgomery bus boycott. As such, we focus on two different aspects of history that are often overlooked. Even though Claudette Colvin’s story included men and women of color, given that March is Women’s History Month we decided to focus on Black women who are left out of textbooks. We begin with a brief history of the other plaintiffs on Colvin’s lawsuit, then provide a timeline of other Black women who have resisted injustices on public transportation. We end with a discussion of the history of segregation in our health care and resources about organizations that currently work to support Black healthcare workers.

|

A Few Well-known Icons vs. The Many Hidden Figures

|

In any major historical movement or moment, there are many people who work to make change happen. For example, Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, and Christine Darden were four Black female Hidden Figures (Shetterly, 2018) who helped launch Americans into space but were not recognized for their contributions until recently. Similarly, although Rosa Parks is the most noted figure in the Alabama bus boycotts, there were many hidden figures, such as Claudette Colvin, who played equally important roles both before and after Rosa Parks’ headline event. There were actually four main plaintiffs -- Claudette Colvin, Aurelia Browder, Mary Louise Smith, and Susie McDonald -- in the 1956 Browder vs. Gayle federal court case that ultimately determined that segregated bus seats were unconstitutional and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. A fifth plaintiff, Jeanette Reese, withdrew her name from the case soon after it was filed after receiving threats from the white community. Teachers can lead students in investigating and creating a diagram or other representation of key movers and shakers in this particular advocacy initiative. Here are more resources about each of these inspirational women:

|

|

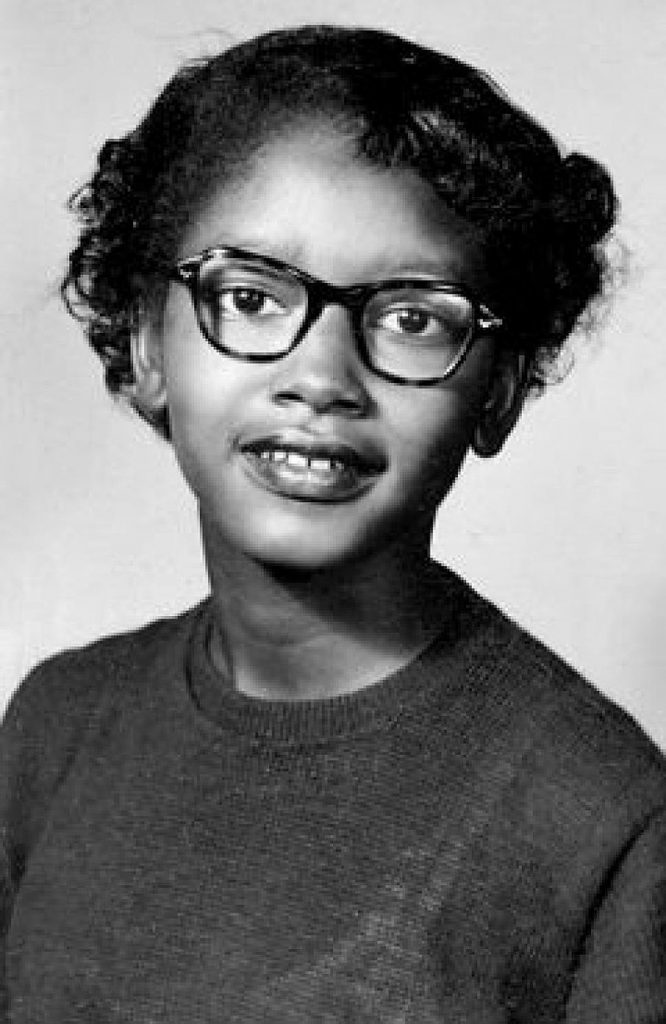

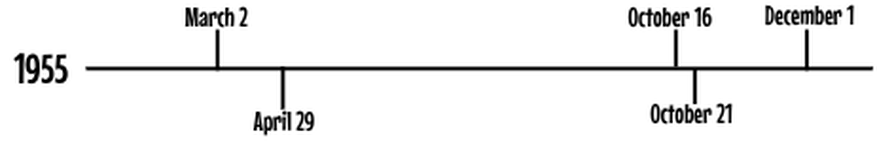

Claudette Colvin was 15 years old when she was arrested on March 2, 1955, for refusing to give up her “Constitutional right” to remain seated on a full bus and not give her seat up for a white passenger. Claudette’s actions inspired and informed Parks’ eventual protest later in the year.

|

Susie McDonald was a business woman and civic activist in her 70’s when she was arrested on October 16, 1955, for violating the bus segregation law in Montgomery, Alabama.

|

Rosa Parks refused to relinquish her seat to a white passenger when the bus became full on December 1, 1955. Her arrest began the 381 day bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama.

|

|

Aurelia Browder was 37 years old when she refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama and was arrested on April 29, 1955. She was an integral member of the boycott by offering her time and her car to those avoiding the buses. She died in 1971, but remained active with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Montgomery Improvement Association, the Women’s Political Council, and the Southern Christian Leadership Council throughout her life.

|

Mary Louise Smith was 18 years old when she, too, refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white passenger on October 21, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama. She remained an activist throughout her life.

|

These four brave women did not act alone. Here are the stories of more women who resisted social injustices on public transportation and were part of the chain of events that inspired Claudette Colvin’s actions. Using the linked resources, share the stories of these women with students.

After learning about these “hidden figures,” discuss together as a class: Why do we not have these women in our history books? Why do we only hear about Rosa Parks’ efforts in the Montgomery bus boycott? Who decides what we learn in history? How can these women inspire us to take action in our own lives?

After learning about these “hidden figures,” discuss together as a class: Why do we not have these women in our history books? Why do we only hear about Rosa Parks’ efforts in the Montgomery bus boycott? Who decides what we learn in history? How can these women inspire us to take action in our own lives?

- 1854 Elizabeth Jennings Graham: Graham was a 24 year old schoolteacher boarded a bus without a “Colored Persons Allowed” sign on it. When the conductor told her to get off, she refused and was forcibly removed.

- 1863 Charlotte L. Brown: Brown boarded a horse-drawn streetcar on April 17 to go see a doctor in San Francisco. When the conductor asked her to leave, Brown said she has a “right to ride” and did not intend to move. She would go on to sue and win cases against Omnibus Railroad twice and paved the way for other African Americans in San Francisco to challenge the privately owned streetcars’ racists practices. Primary documents of her court case can be found here.

- 1884 Ida B. Wells: Wells sued the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Company after the conductor insisted she move her seat from the ladies’ car to the smoking car at the front of the train on May 4. When Wells refused, she was forcefully removed and all of the white passengers applauded. Though she won her case in the local circuit court, the railroad appealed to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, which reversed the ruling.

- 1904 Maggie Lena Walker: Walker was an African American entrepreneur and civil leader that became the first woman ever to establish and lead a bank in the U.S (The Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank in Richmond). Walker was one of the organizers of the boycott that protested the Virginia Passenger and Power Company's segregation policy. The boycott was so successful that the company went bankrupt within one year.

- 1941 Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya: Chattopadhyaya was an Indian diplomat visiting the U.S. as a distinguished guest when a ticket collector in Louisiana ordered her to move from the whites-only section of a segregated train. She replied, “I am a colored woman obviously, and it is unnecessary for you to disturb me for I have no intention of moving from here.” The ticket collector replied that she was Asian, but ultimately did not make her move.

- 1944 Irene Morgan: Morgan refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a bus headed for Baltimore, Maryland on July 16 and was arrested. She tore up the arrest warrant, but eventually pled guilty to resisting arrest, though refused to plead guilty for violating Virginia’s segregation laws. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Morgan’s favor on June 3, 1946 in Morgan v. Virginia.

- 1949 Jo Ann Robinson: Robinson was an English professor at Alabama State College and civil rights activist who became President of the Women’s Political Council (WPC) after she was verbally assaulted by a bus driver in 1949. When Parks was arrested in 1955, the WPC was pivotal in the launch of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Robinson and others printed and distributed 35,000 leaflets to over 42,000 Black residents to spread word about the boycott.

- 1952 Sarah Louise Keys: Keys, a Women’s Army Corps private first class was traveling from New Jersey to North Carolina on August 1 when she was told to give up her seat for a white Marine. When Keys refused, the driver emptied the passengers of the bus onto another vehicle and refused to allow Keys to board the new bus. She was arrested and fined $25 for disorderly conduct. Eventually, she won her case before the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1955 in Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company.

Segregation in Hospitals

|

In this biography, Lesa Cline-Ransome highlighted the devastating death of Claudette’s sister Delphine and mentioned how Delphine went to St. Jude’s hospital because “they treated both Black and white patients equally” (p. 16). The St. Jude Catholic Hospital in Montgomery Alabama was opened in 1951 by Father Harold Purcell as the first integrated hospital in the southeastern United States.

Although we knew that hospitals were segregated, we became curious about the history of hospital integration in the United States. After all, in one of his last speeches, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. expressed the importance of equitable healthcare in Chicago when he said, “of all the inequalities that exist, the injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” |

Here are some resources you and your students can explore together about the history of Black medical care and hospitals in the U.S.:

|

Racism is still prevalent in our healthcare system (Largent, 2018; Reynolds, 2004; Sarrazin et al., 2009) as evidenced by the unequally high COVID-19 pandemic death rates, birthing complications, and environmental health concerns that people of color and their communities experience in the U.S. Over 13% of Americans classify themselves as Black or African American in the U.S. census, but only 5% of all active physicians identify as such (Association of American Medical Colleges). In light of these crises, we wanted to highlight organizations that support and fight for Black/African American physicians, nurses, and medical staff. These groups include the following:

|

Explore the resources in small groups or as a whole class. Discuss with students: Why have we never heard about hospital integration? Did white people protest hospital segregation like they did school segregation? Who fought for equal rights in healthcare? What organizations are still fighting for this right today?

|

Social & Emotional Learning

Understanding Self and Community

|

Dealing with the loss of a loved one and making space to grieve can be very difficult. Grieving a family member’s or friend’s death can be particularly hard for young people. Lesa Cline-Ransome talks about the impact that losing Delphine, her sister, had on Claudette and how hard it must have been to lose a sibling with whom she was very close [7:44 in the interview video]. Although we want to shelter children from pain, it is nearly impossible and may be inadvisable to do so, and many youth are forced to grieve the loss of someone they love. Below is a list of a handful of books for elementary school aged children that deal with loss:

|

After reading one or more of these books, have students do a sketch-to-stretch drawing based on your read aloud by asking students to draw or illustrate what the book made them think about. These drawings should highlight the student’s personal connections to the book. If students feel comfortable, ask them to share what they connected with in a small group. Provide students time and space to discuss their losses with one another and what brought them comfort after the loss.

|

- Bear Island by Matthew Cordell (2001) -- When Louise’s beloved dog, Charlie, passes away she experiences a variety of emotions until she connects with a bear who has experienced a similar loss. This Book Review from the Classroom Bookshelf offers more ideas on how to use this book with younger readers.

- Once a Wizard by Curtis Wiebe (2021) -- This wordless book depicts a young child grieving the loss of a family member. Wordless books may be particularly powerful for narratives of grief because they make room for the reader to create a unique narrative based on their personal connections and perceptions.

- The Heart and The Bottle by Oliver Jeffers (2010) -- After losing her grandfather, a girl puts her heart into a bottle to help with the hurt. But the hurt remains and causes the girl to lose her sense of wonderment as she grows older, until one day she meets another girl and, together, they find a way to free her heart.

- The Purple Balloon by Chris Raschka (2007) -- Chris Raschka learned that children around the world who are terminally ill often depict themselves as a purple balloon when asked to draw their feelings about dying. He used that idea to create The Purple Balloon, which addresses both loss of a loved one and one’s own death.

New Texts & ArtifactsThis section provides instructional ideas connected to Lesa’s She Persisted: Claudette Colvin or in response to the Investigate and Explore sections above. These teaching invitations are designed for teachers who have varying amounts of time in the curriculum to designate to the engagements.

|

Using Multimedia Text Sets

|

A multimedia text set is a compilation of texts and media, often from a variety of genres, that provide multiple perspectives on a topic. Multimedia text sets on historical events might include genres such as primary source documents from historical archives, digital museum tours, video interviews of people involved in the event or with expertise in the topic, biographies and other informational texts, and historical fiction. Below is a list of multimedia texts about Claudette Colvin, Rosa Parks, and the Montgomery bus boycott that you can explore with students to deepen their knowledge on the topic:

|

- Marley Dias Reads Civil Rights Pioneer Claudette Colvin’s Personal Account (YouTube video)

- Claudette Colvin: The Original Rosa Parks (YouTube video)

- Rosa (2007) by Nikki Giovanni, illustrated by Bryan Collier

- Rosa Parks: My Story (1999) by Rosa Parks and Jim Haskins

- Boycott Blues: How Rosa Parks Inspired a Nation (2008) by Andrea Davis Pinkney, illustrated by Brian Pinkney

- Pies from Nowhere: How Georgia Gilmore sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Dee Romito, illustrated by Laura Freeman

- Georgia Gilmore interview

- Claudette Colvin’s fingerprints from her arrest in National Archives: https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/fingerprints-colvin

- Judgment from Browder v. Gayle: https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/judgment-browder-v-gayle

- Rosa Parks Museum Virtual Zoom Tour https://www.troy.edu/student-life-resources/arts-culture/rosa-parks-museum/index.html

One common educational goal is to teach youth how to engage in critical literacy by examining what perspectives and voices are present or missing in texts, what an author’s purpose and bias are in each text, and what systems of power are creating or sustaining inequities in the contexts being described. A multimodal text set allows students to gather information from multiple perspectives, consider how those perspectives compare and contrast with one another, and engage in critical literacy.

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

|

After reading She Persisted: Claudette Colvin, have students do a quickwrite about the Montgomery bus boycott. Ask them to generate questions they still have about the movement or these events in history. As a whole group, create an anchor chart of students’ questions.

|

Jigsaw:

Group 1: Put students into 4-6 groups (group A, B, C, etc.) and have them select one text from the set above. Give each group time to read their text, select important information, and look for answers to their personal questions (from the 1-2 hours activity). Group 2: Regroup the students with one person from each original group in each new group (i.e., one student from A, B, and C, etc.). Each student shares what they learned from the text they read with their first group. Have each group select one question they want to explore about the event and try to answer during this group share. Debrief with the whole class about what they learned and any answers to questions they found. |

Using Cline-Ransome’s writing as a mentor, create a shared book that includes questions students asked and answers they found during the jigsaw. Students can title each chapter with the question, like Cline-Ransome did in She Persisted: Claudette Colvin, and have students answer that question in that section. “Publish” this book and display it for visitors to read and/or place in your classroom library.

|

History of the Civil Rights Movement in Your Community

Colvin’s story and the women we highlighted in the Explore section above demonstrates that many people and events have been ignored in our history. Use Lesa’s biography as inspiration for discovering what occurred in your local community that exposed issues of social injustice. With your students, explore examples of past and present civil rights movements such as worker’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, feminist movements, and indigenous people’s civil rights that occurred in your community or region. What history occurred in your own backyard that you may not even know about?

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

|

As a class, research a local civil rights event or movement that has occurred in your town or region. Research this event together and discuss what occurred. Have students tell their families about these events when they go home.

|

Based on the event or movement the class researched previously, invite a community expert to share their knowledge with the class. This could include someone from the local historical society, a research librarian, someone from a community organization, family members, etc. Work with students to design questions for this expert and interview them either virtually or in person. Students can record what they learned and compare and contrast this event with that of the Montgomery bus boycott.

Ask this expert for additional resources about the event or movement. |

Using the resources provided by your local expert, have students work in small groups to explore these resources and create an exhibit or product per group.

Present these small group products or exhibits in a public physical space, such as the public library, your school showcase space, or as a digital product for other members of the community to see and learn from. |

Kristo, J. V., & Bamford, R. A. (2004). Nonfiction in focus: A comprehensive framework for helping students become independent readers and writers of nonfiction, K-6. Scholastic Professional Books.

Sanders, J., & Shimek, C. (2021). She Persisted: Claudette Colvin. The Biography Clearinghouse.]