|

Entry written by Xenia Hadjioannou and Erika Thulin Dawes on behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse.

|

Research & Writing Process

|

Duncan's Process and Artifacts

|

|

Watch the video to learn more about Duncan’s process of writing and illustrating, specifically:

|

|

|

|

|

Craft & Structure

Translanguaging in Writing

|

Tonatiuh employs translanguaging in his writing by using several Spanish words/phrases in the text. For instance, early in the book, when other kids call Luz “greaser,” Tonatiuh writes “¡Ya basta!” while the illustration indicates that Luz got in a physical altercation with them. And soon after, when Luz’s father is advising him against fighting he adds, “You should always be proud of who you are, mijo.” In a notable departure from many texts that include words from languages other than English, as in these two examples, Tonatiuh does not always provide an immediate translation of the Spanish words into English. This creates a sense of authenticity for the book, as it tells the life story of a Tejano person, who grew up bilingual in Spanish and English, taught himself French during the war, and leveraged his multilingualism to distinguish himself as very valuable to his fellow soldiers and to the war effort. At the same time the practice of rendering translanguaging in writing can also serve to represent and normalize the languaging practices of bilinguals, who often intermigle features from both their languages, particularly when interacting with other bilinguals.

|

WHAT IS TRANSLANGUAGING? |

|

Whereas the use of languages other than English in trade books published in the United States has traditionally been uncommon, the practice is starting to become less rare in recent years. And, authors and illustrators are experimenting with different approaches for representing translanguaging in their books.

In Soldier for Equality, Luz's education and literacy in Spanish, English, and French are explicitly connected to his ability to distinguish himself in the army and beyond, and to engage in activist work. Yet, with few exceptions, the U.S. educational system is not set up to support and develop the bilingualism and biliteracy of students, even those who are already bilingual.

|

After discussing the use of Spanish in the first few pages of the book, ask students to investigate Tonatiuh’s choices in including Spanish in the text. Students can notice when Spanish is included and consider why Tonatiuh chose to include Spanish in the book, as well as why he may have chosen those particular words/phrases. It is also worth noting that Spanish words are denoted in italics in the text and wondering why this choice may have been made. Finally, students can note and query instances when Tonatiuh does not provide a translation and compare them to instances when he does (e.g. “No es justo. It was not right.” when Luz is considering the unfairness of segregated schooling).

You can make available to students a collection of translanguaging books (i.e. texts written primarily in English, with some use of a language other than English) and support them in exploring the different practices. A great resource for identifying and locating such books is the digital library Libros for Language. Students can create their own categories or your class can use the classification system developed by the Libros for Language team.

Key questions to explore:

|

EXTENSION IDEA: Examining Translanguaging Practices Around Us

To extend this examination of the practices of translanguaging, students could

interview bilingual people, focusing on their languaging practices. Another interesting direction could be having older students examine the emerging practices of using translanguaging in mass media (tv, movies, songs) and social media and consider what this may mean in terms of cultural perceptions of bilingualism and translanguaging.

EXTENSION IDEA: Why not Biliteracy?

After engaging in close reading of the text tracing this theme, brainstorm ways in which students’ bilingual identities can be valued and supported in education. This exploration can be connected to the creation of social service announcements about ways to support bilingualism and biliteracy as well as to more traditional argumentative writing opportunities such as essays and letter writing.

To extend this examination of the practices of translanguaging, students could

interview bilingual people, focusing on their languaging practices. Another interesting direction could be having older students examine the emerging practices of using translanguaging in mass media (tv, movies, songs) and social media and consider what this may mean in terms of cultural perceptions of bilingualism and translanguaging.

EXTENSION IDEA: Why not Biliteracy?

After engaging in close reading of the text tracing this theme, brainstorm ways in which students’ bilingual identities can be valued and supported in education. This exploration can be connected to the creation of social service announcements about ways to support bilingualism and biliteracy as well as to more traditional argumentative writing opportunities such as essays and letter writing.

The Craft of Theme Building

|

In the interview, Duncan discusses the different iterations of the book before publication and how, through his progressive drafting, he eventually found Luz’s story in how his experiences changed and transformed him toward becoming an activist.

This theme is interwoven throughout Soldier for Equality; from Luz’s experiences with overt racism and his father’s advice, to the army failing to promote him though he did the work of a commissioned officer, to the continuing segregation practices against Mexican Americans after his return from the war. |

Share with students that Duncan Tonatiuh stated that, for him, this story is about how Luz was transformed into an activist who fought for the rights of Mexican American people. You may also choose to have students listen to the part of the interview where Duncan discusses the evolution of this biography text and its theme (start at 36:24). As a class, comb through the book to locate verbal and pictorial elements that help build the theme across the pages of the book, and create a Theme Building Anchor Chart. It may be helpful to scaffold students using modeling and supported practice through the first few pages, before having them work in collaborative groups to identify elements to add to the anchor chart.

|

Content & Disciplinary ThinkingFighting on Two FrontsSeveral pages of Soldier for Equality are dedicated to Luz’s experience as a soldier during World War I, a service for which he had volunteered, readers learn. In our interview, Tonatiuh further explained that because of his age and the fact that he was married and a father, Luz was not going to be drafted to serve. As noted in the book,

|

“Luz joined the army because he believed it was his duty to serve his country. He wanted to demonstrate that Mexican Americans loved America and would give their lives fighting for it. After they see the sacrifices we are willing to make, the people who mistreat us will start treating us fairly – con igualdad y justicia.”

However, this hope was thwarted both during his army service and after his return. Readers learn that:

Soldier for Equality ends with a reference to the fact that after Luz had “fought with the United States Army in Europe for the ideals of democracy and justice,” he had to fight “on the home front… for those same ideals.” The experience of Luz and other Mexican Americans who fought for freedom and justice overseas only to continue facing racism and inequality in their own military and their own country is unfortunately a situation also experienced by members of other minoritized communities.

Online Resources:

However, this hope was thwarted both during his army service and after his return. Readers learn that:

- Luz encountered prejudicial treatment during his army service, including name calling and the fact that he remained a private, though his assigned position within the intelligence office was for commissioned officers.

- Luz realized that “things had not improved for people of Mexican origin after the war like he had hoped they would”; they still faced segregated schooling and were barred from businesses and restaurants. This prompted Luz to work with other community members to form a civil rights organization to fight for the rights of Mexican Americans.

Soldier for Equality ends with a reference to the fact that after Luz had “fought with the United States Army in Europe for the ideals of democracy and justice,” he had to fight “on the home front… for those same ideals.” The experience of Luz and other Mexican Americans who fought for freedom and justice overseas only to continue facing racism and inequality in their own military and their own country is unfortunately a situation also experienced by members of other minoritized communities.

Online Resources:

- Black Americans Who Served in WWII Faced Segregation Abroad and at Home: Alex Clark’s (2020) article on history.com explores the experience of Black American soldiers in WWII, who had the paradoxical experience of fighting “for democracy overseas while being treated like second-class citizens by their own country.” [teacher & secondary student resource]

- Double V Campaign: This article from newspapers.com provides information about the Double V Campaign, an African American campaign aiming to achieve double victory in the war against nazzism abroad and against discrimination within the US. The campaign was run through the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper. The article includes images of several newspaper clippings related to it. [teacher & student resource]

- The Remarkable and Complex Legacy of Native American Military Service: In this article from the Smithsonian Magazine, Alicia Ault (2020) discusses the persistently high percentages of Native American individuals serving in the US military, references stereotypes (e.g. the warrior myth) and assimilationist practices levied against soldiers of indigenous background, and highlights traditions and tribal rituals practiced by indigenous service members. [teacher & secondary student resource, though the embedded archival images can be productively shared with younger students.]

|

Children’s Books:

|

These resources can be used to support a standalone unit exploring the contributions made by minoritized communities to the US military and critically analyzing the discriminatory practices that have historically marginalized, mistreated, or limited the opportunities of people of color within and outside of the armed forces.

In addition, selected resources or resource excerpts can be used when studying the history of specific conflicts or other historical events. Their inclusion would serve to expand and deepen traditional narratives that tend to omit the contributions of minoritized communities and obscure or erase troubling or unflattering historical facts. |

Minoritized Communities in Today's US Military

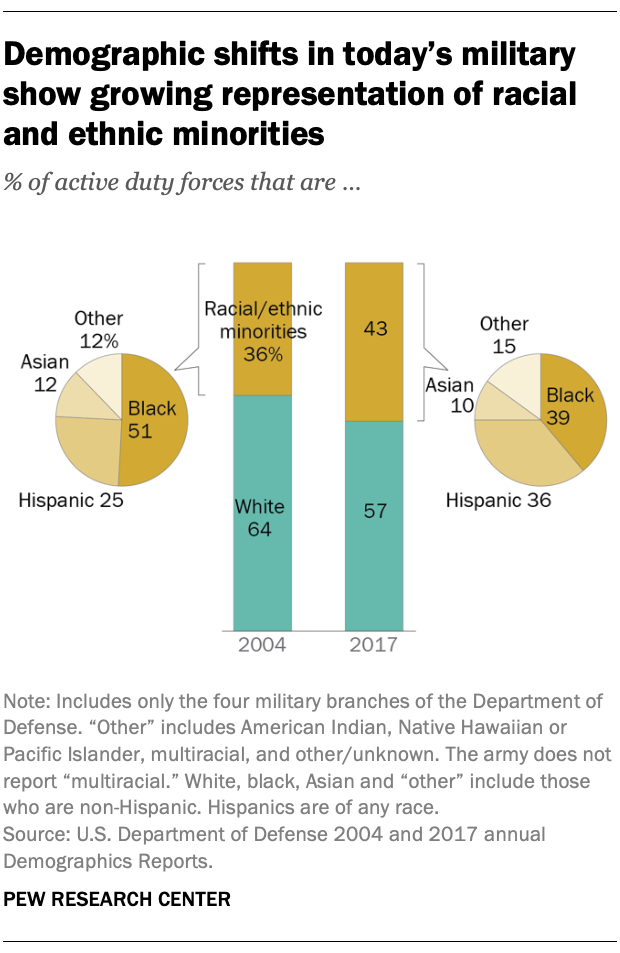

During our interview, Duncan noted that even 100 years later, and though there are many Latinos/as serving in the US forces, they still face obstacles moving through the ranks and are significantly underrepresented in high positions (39:26). This continuous pattern of inequity is worth investigating further.

According to the PEW Research Center (2019) the US Military is becoming increasingly ethnically and racially diverse. As shown in the embedded graph below, in 2017, 43% of active duty forces were black, Hispanic, Asian or another racial or ethnic minority group. This represents a significant uptick from 36% in 2004. Within this group, the percentage of Hispanics rose from 25% in 2004 to 36% in 2017.

According to the PEW Research Center (2019) the US Military is becoming increasingly ethnically and racially diverse. As shown in the embedded graph below, in 2017, 43% of active duty forces were black, Hispanic, Asian or another racial or ethnic minority group. This represents a significant uptick from 36% in 2004. Within this group, the percentage of Hispanics rose from 25% in 2004 to 36% in 2017.

|

However, a 2020 report released by the Defense Department’s Diversity and Inclusion Board indicated that despite the diverse makeup of the enlisted corps, the same is not true of the officer corps. Indeed, according to the report, 73% of all active commissioned officers were white; 8% were Black, 8% Hispanic; 6% Asian; 4% multiracial; and less than 1% Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native. Notably, “the diversity gap widened the higher individuals moved up in the ranks” (Stafford et al., 2001).

Regarding Latinos/as in particular, a 2019 Report by the Congressional Research Service stated that though the percentage of 18% of people of Hispanic origin among the active duty enlisted corps is on par with their share among the country’s general population, “Hispanic officers account for roughly 8% of the officer corps and 2% of General/Flag officers” (p. 20). Resources:

|

These resources can be used to support a standalone unit on the contributions of minoritized communities to the US military and the discrimination they have historically endured (see the Fighting on Two Fronts section above). Information can be used to connect history to the present and draw attention to the persisting patterns of marginalization and discrimination. Beyond its obvious linkages to history subject area standards and objectives, such an exploration can be very productively connected to mathematics and the use of statistical analyses for describing trends and patterns, identifying incongruities, and drawing inferences and conclusions. The resources listed above include several compelling charts that can become the subject of study for middle-grades and secondary students.

Social & Emotional Learning

Social Justice Concerns in Personal Lives and Society

|

Throughout his life, Luz identified injustices levied against Mexican Americans, and engaged in purposeful actions to work against these injustices and promote equity. In Soldier for Equality, readers encounter several instances of prejudice and discrimination against Luz, because of his status as a Mexican American. For instance,

Readers also get to see purposeful actions Luz is taking to fight against these injustices, including:

|

As a class, create parallel lists of (a) instances of prejudicial treatment Luz encountered and (b) purposeful actions he took to work against those injustices and bring about equality and fair treatment.

At the micro/personal level: Invite students to locate instances of prejudicial treatment and unfairness in their daily lives. Are there certain people who are persistently teased, gossiped about, called names, bullied, or excluded? What would be some specific purposeful actions they could take to work against those patterns of mistreatment and exclusion? At the macro/social level: Invite students to locate instances of prejudicial treatment and injustice in modern society. What are some aspects of modern society where unjust treatment is still an issue? Who is taking purposeful action to combat these injustices? What actions are they taking? Depending on the age of the students and on the time available, this can lead to inquiry projects into the lives of modern day activists and/or the work of social action organizations such as LULAC and the NAACP. |

New Texts & ArtifactsTraditional Art MotifsA distinctive characteristic of Duncan Tonatiuh’s picture books are his stylized illustrations, which are inspired by Mixtec Pre-Columbian art, and particularly the Mixtec Codices. In this interview with KidLit TV, Duncan Tonatiuh discusses how Mixtec traditional art continues to inspire his work:

|

|

Resources about the Mixtec Codices, offering information and images:

|

|

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

|

Invite students to examine images from the Mixtec Codices available through the resources above and note (a) stylistic echoes from the codices into Duncan Tonatiuh’s illustrations and (b) ways in which Tonatiuh has reimagined the style to illustrate modern picturebooks.

The KidLit TV video can be shared at the conclusion of the exploration to elucidate the artist’s own perspective. |

Share with students other picturebooks that incorporate and reimagine traditional art motifs in their illustrations. Author notes and complementary resources can help students notice the motifs and consider the effect of their use. Some examples:

Divide your students up into small groups, with each group responsible for reading and discussing one or more of the titles. Questions for students to consider include:

Invite groups to take digital pictures of 2-3 pages or spreads that exemplify how the illustrator has incorporated visual motifs in the picturebook. They can then embed them into slide-decks and use the tools in the Draw and Insert menus to add annotations capturing their responses to the exploratory questions above. The slide decks can then be used to support group share-outs to the class. Extension: The slide decks can be converted into narrated presentations and exported as video files akin to the short informative videos available in museums. If your school has a media gallery, the videos can be uploaded there and a sticker with a QR code linking to its corresponding video can be placed in the inside cover of each book. |

Ask students to consider the presence of traditional art motifs in their own homes and communities. Students can keep observation journals in which they sketch and describe the examples that they see. Or, they can use phones or digital cameras to take pictures.

Invite students to create art incorporating the traditional art motifs present in their communities and significant in their lives. Students could work individually to create a portrait of their family or collectively to create a community mural. Discuss with students how when you use traditional motifs, you are not simply recreating them, you are using them to tell your own stories, drawing upon a dynamic representation of cultures. Students’ work can be shared informally but also through a Gallery Walk event with other classes and/or with the community as invited guests. |

Teachers as Activists

José de la Luz Sáenz was deeply committed to the profession of teaching and, for him, teaching went hand in hand with activism. He viewed education as a pathway to social justice and worked throughout his life in the role of a teacher activist, providing access to language and literacy instruction and organizing and advocating for equity and access in educational settings.

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

|

Read or reread Soldier for Equality: José de la Luz Sáenz and the Great War and ask students to make note of the meaning that education, language, and reading and writing had in his life. Record students' thoughts on a two column chart with one column labeled ‘claims’ and the second column labeled ‘evidence from the book.’ Next, pair students up, asking students to interview each other about the roles of language and literacy in their lives. Prior to conducting the interviews, brainstorm a list of questions to ask. Questions could include:

|

The text set outlined below features the life stories of teachers who, like Luz, also served as activists. Divide students into small groups, each group responsible for reading one of the picturebooks listed below.

Provide each group with a graphic organizer on which to record notes about the subject of their biography. Students can record: the name, birth, and death dates of their subject; where their subject lived and worked; key achievements of their subject; challenges faced by their subject; beliefs about education held by their subject. To share their learning about these teacher activists with their classmates, ask each group to create and perform a monologue in the voice of their subject. The monologue should highlight the information captured in their graphic organizers. |

As an extension of the text set exploration of teacher activists, engage students in a discussion of all the people that serve as teachers in their lives. In which settings do they learn beyond school? Who are the people who mentor, guide, and teach them in all the realms of their lives? Invite students to consider what they could compose, create, or make to honor and celebrate their teachers. Possible projects could include:

|

Hadjioannou, Xenia & Thulin Dawes, E. (2022). Soldier for Equality: José de la Luz Sáenz and the Great War. The Biography Clearinghouse.