|

Entry written by Xenia Hajioannou and Mary Ann Cappiello, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse.

|

Research & Writing ProcessWho is Steve Sheinkin?

|

Steve's Process & Artifacts

|

|

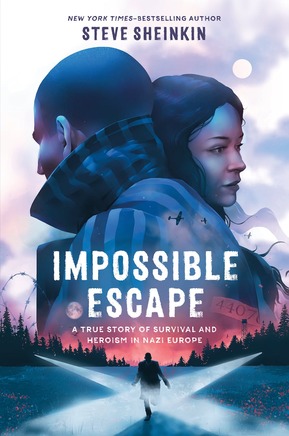

Watch the interview with Steve Sheinkin to learn more about his inspiration, process, and research for writing Impossible Escape: A True Story of Survival and Heroism in Nazi Europe. In the recording, you can hear Steve discuss:

|

Craft & Structure

Foreshadowing

|

Foreshadowing is a craft technique used by authors of narrative text to offer readers a glimpse into the story to come. Sometimes ambiguous and others explicit, these hints can be valuable in focusing and sustaining the reader’s attention, sharpening their analytical awareness, and keeping them reading on.

Foreshadowing is used on several occasions across Impossible Escape, most often at the very beginning or very end of chapters. Some instances of foreshadowing forewarn of terrible things to come whereas others offer hope in times of despair. An early example of foreshadowing appears at the end of the prologue when, after reading an in-the-moment narration of Rudi’s attempt to leave Slovakia and make his way to Great Britain, the reader encounters the foreboding coda: “It was a smooth start to what would prove to be a journey into hell” (p.x). This foreshadowing statement grabs the reader’s attention and compels us to continue reading, while at the same time filling us with dread about what promises to be a harrowing story. At the page turn, we encounter another foreshadowing statement as we begin reading the first sentence of chapter 1. This one softens the sharp edges of dread and soothes the reader forward: “RUDI WOULD FIND A WAY to fight Adolf Hitler. It can be said, without risk of exaggeration, that he would go on to be - while still a teenager- one of the great heroes of the entire Second World War” (p. 5). |

Point out these early instances of foreshadowing to students and encourage them to consider:

Further, encourage students to note foreshadowing in other texts, movies, and TV shows and examine how they operate. They could also ask questions about style and frequency of foreshadowing and compare effective and less effective applications. Students can also experiment with foreshadowing in their own narrative writing. |

Punctuating Narrative with Exposition

|

Throughout Impossible Escape, Steve Sheinkin builds a tight narrative filled with action. Reading like a movie or a novel, the storyline builds tension, takes twists and turns, and moves towards a dramatic turning point and conclusion. But the book isn’t only the storyline. At times, Sheinkin zooms in on a single event, within a single story, and then zooms out to provide a larger context or reveal a pattern across people and time.

For example, on page 24, an old woman approaches Rudi, who is locked up in a small cell after getting beaten up and arrested in Hungary after fleeing Slovakia. She addresses him as “Mr. Jew” as she drops some food and cigarettes in his cell. Then Sheinkin begins to zoom out from this single event to note: “A kind gesture, but ominous also. He wasn’t a teenager anymore, not to most of the people in what he’d thought was his country.” In a further zoom out, Sheinkin goes on to explain that antisemitism was “hardly new in Europe,” and provides a brief overview of antisemitism across the centuries, from the medieval period to the 20th century. Sheinkin leverages the dramatic moment within his narrative to provide readers with necessary background knowledge to understand more deeply the dangers Rudi and Gerta and their friends and families faced. |

Ask your students what they notice about this scene on page 24 and the exposition that follows. What do they learn? Why did Sheinkin pause the narrative? Why is this information important? After having that conversation, play the portion of our interview with Sheinkin, where he discusses how, why, and when he punctuates narration with exposition: 00:22:36.190 --> 00:27:47.800.

After discussing the video segment, have students

|

Euphemisms to Obscure and Bureaucratize Injustice

|

The systematic effort to annihilate European Jews during World War II was dubbed by the Nazis as the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” (“Endlösung der Judenfrage”), often encountered in the shortened “Final Solution” (“Endlösung”). Though the “Final Solution” was nothing short of the systematic imprisonment, torture, and mass murder of a group of people, the term itself bears little indication of the genocidal savagery it names.

It is important to note that, during this period, many others were also systematically relocated and murdered, such as Roma, Sinti, trade unionists, the disabled, and the LGBTQ community. Further information about the persecution of these communities can be found among the pages of the Holocaust Encyclopedia of the United States Holocaust Museum:

The “Final Solution” euphemism attempts to sanitize the atrocity of its true nature, presenting the system put in place to perpetrate mass murder almost as an objective, bureaucratic procedure, devoid of ethical content. And in doing so, it attempts to absolve perpetrators from recognizing and facing the immorality of their actions. There is a long history of using euphemisms in sociopolitics to obscure and bureaucratize unjust, even inhumane practices. |

Link an exploration of euphemisms to Social Studies to consider moments in US history characterized by systematic injustices. What language did the perpetrators of those injustices use to obscure the wrongdoing and create a facade of legitimacy? Primary Sources, including excerpts from official documents and periodicals of the time, can provide valuable sources for such explorations.

Examples to consider:

Beyond historical euphemisms, students may be encouraged to considered modern euphemisms that have been used to describe unjust, morally problematic practices such as “enhanced interrogation” instead of torture and “repatriation” instead of forced expulsion of undocumented immigrants. |

Content & Disciplinary ThinkingThe Destructive Power of Big LiesEarly on in the book, Steve Sheinkin explains that Hitler “endlessly echoed” untruths and conspiracies against Jewish people, noting that Hitler wrote explicitly about “the power of what he called a ‘big lie’ to influence at least part of the public” (p. 25). Sheinkin also quotes one of Hitler’s “primary rules” as listed in a psychological profile constructed by the American Office of Strategic Services: “People will believe a big lie sooner than a little one; and if you repeat it frequently enough people will sooner or later believe it” (p. 25).

|

Hitler’s relentless use of “a big lie” to villainize Jewish people was at the heart of the Holocaust and fed the complicitness of others. The big lie held such sway that even when untruths and conspiracies were exposed as such, it did not stop them from spreading. And, as we can see in the episode between Gerta and Marushka early on in the book (p. 8-9), they were even adopted by people whose lived experience told them otherwise; Marushka and her family embraced Nazi propaganda against Jewish people even though their experience with Gerta’s family and other Jewish people in their community disconfirmed it.

Hitler’s “big lie” still persists in the rhetoric of Holocaust deniers, who claim that the Holocaust did not happen, willfully dismissing the extensive historical evidence of the atrocities committed against Jewish people and other groups. Sheinkin captures this aspect of Hitler’s “big lie” by including in the book’s epilogue Rudi Vrba’s testimony during the Canadian trial of a Holocaust denier in 1985. After the trial, Rudi asserted that “the only way to fight big lies” is “with aggressive doses of the truth” (p. 216).

Explore how lies and conspiracy theories impact people’s lives and the social fabric of communities and nations by choosing one or more of the following activities.

Hitler’s “big lie” still persists in the rhetoric of Holocaust deniers, who claim that the Holocaust did not happen, willfully dismissing the extensive historical evidence of the atrocities committed against Jewish people and other groups. Sheinkin captures this aspect of Hitler’s “big lie” by including in the book’s epilogue Rudi Vrba’s testimony during the Canadian trial of a Holocaust denier in 1985. After the trial, Rudi asserted that “the only way to fight big lies” is “with aggressive doses of the truth” (p. 216).

Explore how lies and conspiracy theories impact people’s lives and the social fabric of communities and nations by choosing one or more of the following activities.

If you have 1-2 hours . . .When reading the book, stop to consider Hitler’s theory about how “big lies” work, coupled with Hitler’s “primary rule” about lies developed by the Office of Strategic Services.

How did Hitler use “big lies” to expand his political power and support his ambitions for European domination? Have students explore the following documents to discuss lying as a political strategy:

|

If you have 1-2 days . . .How do we identify big lies today?

Engage your class in collaborative work to develop frameworks for safeguarding individuals, communities, and nations from getting duped by big lies and conspiracy theories. Invite your school librarian to work with your class to review information and media literacy skills, drawing on curated resources from organizations such as the following: To share their frameworks, students can create Public Service Announcements through posters, jingles, and video clips. Or, they could plan and host events in your community. |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . .How can recognizing lies large and small help our society today?

Offer students the opportunity to engage in an exploration of a contemporary big lie. Again, working with your school librarian, curate carefully vetted texts appropriate for your students using the databases available to you through your school/district library services and community library services. Topics could include:

After students have completed research, have them make presentations to one another about the dangers of each particular conspiracy theory and/or big lie, and how they create mistrust within the social fabric. |

A Text Set Exploration of Young People's Experiences during World War II

As dramatic as Rudi and Gerta’s experiences were, and as important as Rudi’s escape was to the lives of over 200,000 Hungarian Jews, they were also just two teenagers among millions of young people around the world whose lives were disrupted and forever transformed by the rise of Nazi Germany and the events of World War II.

After your class completes Impossible Escape, have students join book clubs to read nonfiction or historical fiction about other young people during World War II. While it is helpful to have the book choices for students in the classroom, you may be able to curate reading opportunities through your local and/or statewide library network of ebooks. You may also want to start with the book club format and simply include Impossible Escape as one of the options within the text set.

|

Middle Grade & YA Nonfiction:

|

Middle Grade & YA Historical Fiction:

|

As students explore these texts, offer them opportunities to discuss their reading in book-based groups and in jigsawed groups. As students compare and contrast the events they are reading about, have students track this information on a map and have them co-create a timeline of events. Have students discuss what themes emerge across their books and what new questions the books prompt. To share their learning, students may want to write letters to one another from the perspectives of people within their books.

You could also use this as an opportunity to invite community elders into your classroom to discuss their own childhood and teenage experiences and memories of World War II. If possible, record these conversations to share with future generations of young people in your community.

You could also use this as an opportunity to invite community elders into your classroom to discuss their own childhood and teenage experiences and memories of World War II. If possible, record these conversations to share with future generations of young people in your community.

Social & Emotional Learning

Embracing Point of View in Nonfiction Writing

Nonfiction writing is often described as factual and objective, where the author and their perspective have no place. However, as noted in NCTE’s (2023) Position Statement on nonfiction literature, “though nonfiction has traditionally been thought of as offering an authoritative treatment of its topics, it is important for readers to understand that nonfiction, no matter how well researched and thorough, represents the authors’ perspectives and points of view.”

In Impossible Escape readers can infer how Steve Sheinkin is positioned toward the events and the issues at hand by noticing how he chooses to describe them. For instance, he explicitly characterizes antisemitic stereotypes as garbage (p.8) and being “rooted in ignorance and lies” (p. 24). Similarly, when Sheinkin writes about what Gerta did during the last months of the war, his admiration for her is clear when he notes: “Even after all her close call, she chose not to play it safe.” Steve Sheinkin as the author becomes even more clearly visible when he addresses the reader by asking rhetorical questions that pull us out of the narrative and prompt us to grapple with some weighty material. In our interview, Steve offers some valuable insight into his decision to use rhetorical questions (starting at 30:55). At the very end of the book, Steve Sheinkin admits that he struggled with figuring out how to conclude the book, thinking that he needed to come up with a way to sum up the book with “some profound message to apply to daily life” (p. 219) and admitting that “this last little section was the hardest for me to write” (p. 219). You can hear Steve discuss this decision in the interview, starting at 34:39. In the end, he took a lesson from Rudi Vrba himself who would say that “the story is the thing” and encourage his audience to draw their own conclusions and interpretations. It is an interesting contrast to traditional storytelling that often ends with an explicit lesson or moral. |

Invite students to look for the author while reading Impossible Escape as well as other nonfiction texts. How do those glimpses help readers infer the book creators’ emotional and intellectual positioning toward their topic?

After finishing the book, encourage students to sit with the last few sentences: “Everything is in the story. You read the story. You know what to do” (p. 219). Invite them to respond in any way that makes sense. That could involve writing, drawing, painting, or recording. Plan a gallery walk or other opportunities for sharing these responses. When students are writing their next nonfiction text, encourage them to engage emotionally with their material, and to insert themselves in some way in the text. |

New Texts & ArtifactsAt the beginning of Impossible Escape, Rudi and Gerta live in the same town and attend the same school. Gerta’s crush on Rudi goes unrequited, a situation common to teenagers. Soon the events of the war force their separation, and they don’t reunite until after Rudi’s daring escape from Auschwitz towards the end of the war. Throughout the book, Sheinkin weaves back and forth between their dramatically different experiences. Gerta does not bear witness to the same level of horror or encounter the violence Rudi does, but she seeks out roles and takes daring risks to keep fellow Jews hidden from the Nazis. Each has experiences where they learn they can and can’t trust other people, a common rite-of-passage for teens, but one that is a life or death lesson during their lifetime.

|

Writing nonfiction about more than one person at once may not always be an obvious or even possible choice for nonfiction writers focusing on life stories. The historical evidence does not always offer comparable information. Nevertheless, offer your students the opportunity to practice writing nonfiction from the perspective of more than one person, choosing one or more activities listed below.

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

|

Have each student make a list of the things they did over the course of the day before arriving in your class.

Next, place students in pairs, and have them share their list of activities. Each can add new details based on hearing the other’s list. Have students then write the story of their day, weaving back and forth between their different experiences. For practice in biographical writing, have each write the other’s story. Once students have the basic events down, play the portion of the interview in which Sheinkin shares the details he wishes he could find when researching to build scenes in his nonfiction narrative (00:10:16.700 --> 00:14:08.209). Next, ask students to include additional descriptive information, like the kind that Sheinkin seeks. This may prompt questions for the other (What did they see out the bus window? What did they eat for breakfast? Who did they eat lunch with?). Invite students to share their pieces with other pairs. |

Engage students in an exploration of perspective and point-of-view in “true” stories by engaging their friends or family members in discussion about a particular event.

Invite students to interview 2 people about a shared but relatively minor experience they had. Students can interview family members, friends, neighbors, or even teachers in the school. Record the interviews to capture details. In class, have students write a short work of narrative nonfiction on the specific event, including the experiences from both people involved. Students may have follow-up questions like the additional descriptive details Sheinkin discussed in the interview. Allow them time to ask those questions and add them to their pieces. Provide students the opportunity to share their narrative pieces and to discuss what they learned about doing research and writing based on people’s memories of events. |

Engage students in an exploration of perspective and point-of-view in “true” stories by engaging them in research about a historical event. Students might want to make a list of events they are interested in exploring and join small groups to author narrative pieces together. Working with your school and public librarian, curate resources that students can explore in class, and have students write short pieces of researched narrative nonfiction about their event, drawing from the perspectives of at least two participants.

Have students share their final pieces in a community read at your school, local historical society, or public library. |

Hadjioannou, X., & Cappiello, M.A.. (2023). Impossible Escape. The Biography Clearinghouse.